The fight over who profits from Sonny & Cher’s classic hits has moved from the recording studio to the courtroom, where a 1970s divorce deal is now colliding with modern copyright law. At stake are millions of dollars in annual royalties from songs such as “I Got You Babe” and “The Beat Goes On,” and the power to decide how those works are used in films, advertising, and reissues. The case pits Cher against the estate of her late ex-husband Sonny Bono, led by his widow, former congresswoman Mary Bono, in a dispute that tests whether long-ago agreements can withstand federal “termination” rights designed to let authors and their heirs reclaim copyrights decades later.

High Stakes in a Classic Catalog

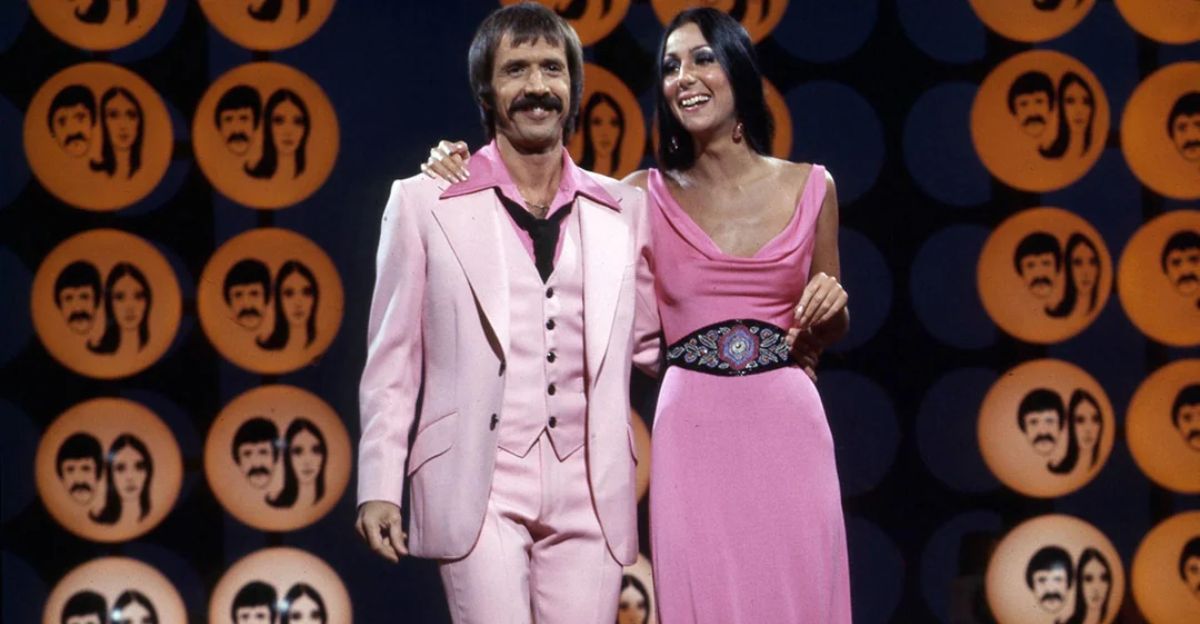

The royalties under dispute flow from both compositions and recordings in the Sonny & Cher catalog, which continues to generate significant income decades after the duo’s 1960s and 1970s success. Beyond the money, the case will shape who controls licensing decisions for the catalog going forward—an increasingly important issue in an era of booming catalog sales and global synchronization deals.

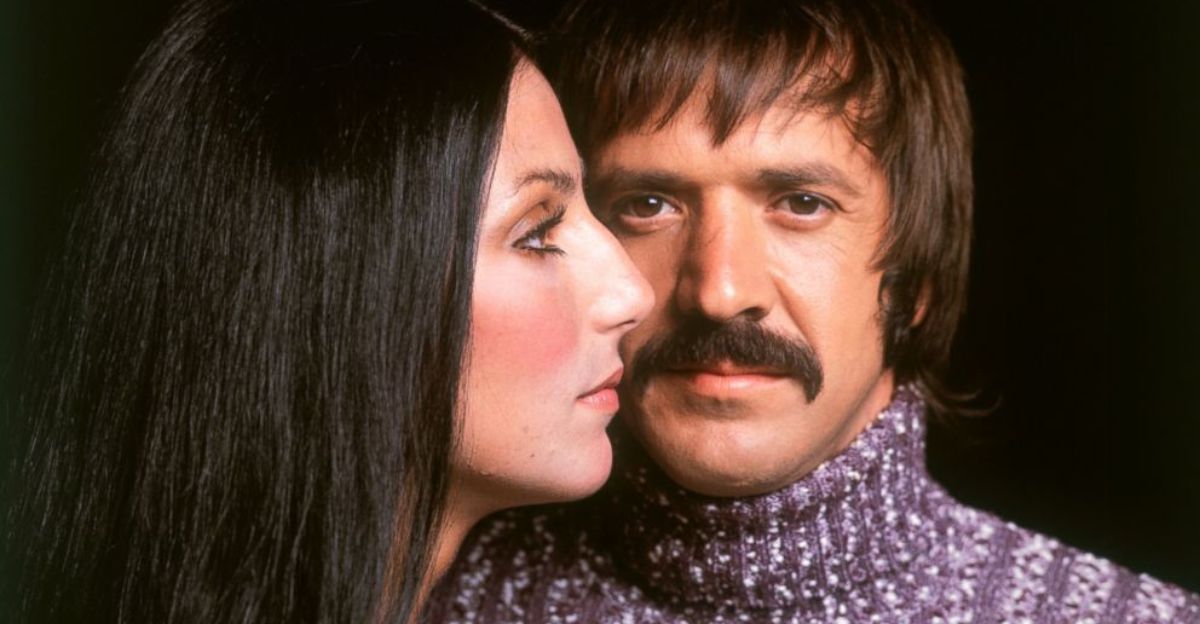

Cher’s share of the royalties traces back to the couple’s rise from a pop partnership to mainstream stars, followed by a personal and professional split in the mid‑1970s. When their marriage ended, the division of their creative legacy was written into a divorce settlement that would later become the cornerstone of Cher’s legal position.

A Divorce Deal Meets Termination Law

Cher and Sonny Bono married in 1964 and built an international following as Sonny & Cher before their act and marriage fell apart. Their 1978 divorce, finalized under California law, included a marital settlement agreement granting Cher 50% of the composition and recording royalties from their joint catalog. That contract divided not only their property and income at the time, but also future royalty flows from the songs they had created together.

Sonny Bono died in a skiing accident in 1998, and his royalties passed into a trust overseen by Mary Bono in California. Decades later, federal copyright law opened a new door: beginning in 2018, Sonny’s heirs became eligible to use termination rights to “take back” publishing rights that had been granted years earlier. His family began serving termination notices on the catalog, arguing that Congress intended authors and their heirs to be able to reclaim rights regardless of earlier private arrangements. Those notices framed Cher’s interest as something that should disappear once the underlying grants were unwound, effectively routing the full royalty stream back to Sonny’s successors.

Cher countered that the 1978 divorce settlement was a binding property division that could not be undone by later statutory termination. In October 2021, she sued in federal court in Los Angeles, contending that the estate had improperly cut off payments owed under the divorce agreement. The dispute quickly became a test of how federal copyright provisions interact with state‑law marital contracts.

Judge Backs Cher’s Contract

On November 26, 2024, U.S. District Judge John A. Kronstadt issued a final judgment that largely sided with Cher. Applying California contract law, he held that the 1978 divorce agreement remains enforceable and that Sonny’s heirs could not use the Copyright Act’s termination provisions to cancel Cher’s 50% share of composition and recording royalties. In his view, the termination notices “did not terminate or otherwise have any effect” on the marriage settlement, meaning the state‑law contract still governs how the Sonny & Cher royalty pool is divided.

The court also addressed how money flows in practice. In 2022, Cher sold her royalty interests to Irving Azoff’s Iconic Artists Group, but the judge ruled that royalty payments must continue to be made to Cher directly, consistent with the 1978 agreement. She then transfers funds to Iconic. That structure maintains Cher’s contractual position at the center of the payment chain and preserves her leverage over approvals tied to the catalog.

The ruling went beyond money. Judge Kronstadt confirmed that Cher retains approval rights over “any and all third‑party contracts with respect to the musical compositions.” She continues to have authority to vet aspects of licensing and other agreements, while Mary Bono’s side gains only a limited role in administration. The decision thus preserves Cher’s significant influence over how iconic tracks are deployed in future projects, even as ownership and administration roles evolve.

Narrow Win for Heirs and Financial Fallout

Mary Bono did win on one discrete issue. The court held that Sonny’s heirs have “sole discretion” to choose the royalty administrator, including an entity they own, giving the estate control over who manages royalty accounting and related back‑office functions. Cher, however, retains the right to object based on the “reasonableness of administration fees” and the administrator’s “credentials and qualifications,” creating checks on that authority. The 50–50 split of royalties and Cher’s direct payment rights remain intact.

The judgment also addressed money that had already been withheld. Judge Kronstadt ordered Sonny Bono’s estate to pay Cher more than $187,000 plus interest for publishing royalties that were not paid while the termination dispute unfolded. Because Cher prevailed on nearly all contested issues, the court designated her the “prevailing party” and awarded her litigation costs on all but the single claim where the heirs succeeded on administrator selection. Mary Bono may recover costs tied to that narrow point, but the overall fee allocation reflects a lopsided outcome and adds financial pressure as the estate weighs its next steps.

Looking Ahead: Appeals and Industry Implications

Mary Bono’s attorney, Daniel Schacht, has sharply criticized the decision, arguing that the court “got the law wrong on copyright terminations” and stressing that “it is important that authors and their heirs have the rights that Congress intended.” He has vowed to appeal, signaling that the U.S. Court of Appeals will likely be asked to reconsider how far federal termination rights can go when they intersect with older divorce settlements and similar private bargains.

Legal observers say the ruling could influence how courts treat long‑standing marital agreements involving intellectual property. By enforcing a 1978 California settlement over later termination notices, Judge Kronstadt suggested that contractual royalty splits can, in some circumstances, survive statutory “take‑back” efforts. Artists, ex‑spouses, estates, and catalog investors are now reassessing how old settlements may constrain future termination strategies and affect negotiations around legacy works.

The dispute also reflects Sonny Bono’s unusual path from chart‑topping performer to mayor of Palm Springs and Republican member of Congress, and then Mary Bono’s own congressional career. Questions about how public figures manage creative assets—and what happens when divorce, estate planning, and copyright law are not fully aligned—hover over the case.

Because Sonny & Cher’s music is licensed worldwide, rights holders and collecting societies in other countries are watching closely, even though foreign territories operate under their own rules. The core tension between contract and statute—whether federal termination rights can override private divorce deals—will remain a central issue as Mary Bono’s promised appeal moves forward. For now, Cher’s victory signals that detailed, decades‑old agreements can still determine who profits from cultural touchstones, and it underscores the need for artists and their families to plan for legal frameworks that outlast their personal relationships and even their lifetimes.

Sources

Billboard Nov 2024 royalties ruling coverage

Music Business Worldwide Nov 2024 Cher settlement

Variety Nov 2024 Cher-Bono judgment

KESQ/City News Service Dec 2025 follow-up reporting

Law360 May 2024 royalties award

Wikipedia Sonny & Cher biographical reference

U.S. District Court Central District of California final judgment Nov 2024