The opening chords hit and, in an instant, decades fall away. For many Baby Boomers, certain songs do more than trigger fond memories; they reopen the emotional landscape of their youth, from sunlit optimism to political upheaval and cultural change. These tracks, all recorded between the mid-1960s and late 1970s, chart a journey from innocence to disillusionment, from idealism to reflection, and still act as a bridge between who they were and who they became.

California Dreams and Cracks in the Surface

When The Beach Boys released “Good Vibrations” in 1966, its first shimmering notes seemed to bottle the mood of the moment. Crafted by Brian Wilson, the track fused bright pop with early psychedelic experimentation, evoking images of California beaches, first dates, and endless summers. For many Boomers, it became the soundtrack to a world that still felt open and full of promise.

Yet the timing was pivotal. The song arrived just as the Vietnam War was escalating and the broader cultural upheavals of the late 1960s were gathering force. In retrospect, “Good Vibrations” stands as a final snapshot of a more innocent era. Its lush harmonies and buoyant tone represent the last widely shared sense of optimism before the darker realities of war, political division, and generational conflict took center stage.

Protest, Inequality, and a Troubled Nation

By 1969, that optimism had frayed. Creedence Clearwater Revival’s “Fortunate Son” captured the anger of a generation watching working-class draftees sent to Southeast Asia while many from privileged backgrounds avoided combat. John Fogerty’s searing vocal made the song an unmistakable protest, not only against the war but against a system perceived as fundamentally unfair.

The track’s later life adds another layer for Boomers. Often heard today at patriotic celebrations and backyard gatherings, its use can feel jarring when set against its original anti-war message. For those who lived through the era, this shift underscores how the rebellious edge of their youth culture has sometimes been smoothed over or commercialized, even as the song’s underlying critique remains embedded in its lyrics.

At the same time, other recordings spoke to the need for comfort amid turmoil. Released in 1970, “Bridge Over Troubled Water” by Simon & Garfunkel arrived during intensified Vietnam protests and ongoing civil rights struggles. Its soaring vocals and gospel-tinged piano turned a simple promise of support into a kind of emotional refuge. For many listeners, it offered reassurance at a moment when social cohesion felt fragile, becoming an enduring hymn to solidarity and care.

Idealism, Loss of Innocence, and Lingering Questions

In the early 1970s, John Lennon’s “Imagine” distilled the hopes of a generation into a spare piano ballad. Issued in 1971, the song laid out a vision of a world without borders, religious divisions, or economic inequality. For Boomers who believed they could fundamentally reshape society, it crystallized their highest ideals: peace, unity, and a shared humanity.

Over time, the track has taken on a bittersweet quality. Many of Lennon’s dreams remain unrealized, and the distance between the world the song envisions and present realities highlights both the power and the limits of that generation’s aspirations. Yet “Imagine” endures precisely because it continues to challenge listeners to consider what a more peaceful world might require.

That same year, Don McLean’s “American Pie” offered a sprawling reflection on how much had already changed. At more than eight minutes, the song looks back to “the day the music died,” a reference to the 1959 plane crash that killed Buddy Holly, and traces the evolution of rock and roll alongside the loss of cultural innocence. For many Boomers, it reads as a chronicle of their own journey from the hopeful late 1950s through the upheavals of the 1960s.

Its enigmatic verses turned the song into a kind of generational riddle. Listeners debated the identities of its “jester,” “king,” and other figures, using their interpretations to make sense of both musical history and their own coming-of-age. The mystery around “American Pie” became part of its appeal, inviting repeated listening and reflection.

Changing Intimacy, Freedom, and the Darker Side of Success

As the 1970s progressed, popular music also mirrored shifts in private life. Marvin Gaye’s 1973 hit “Let’s Get It On” is often remembered as a romantic anthem, but for many Boomers it also signaled a broader rethinking of closeness. The song’s frankness about emotional connection aligned with changing attitudes toward relationships, while Gaye’s vocal vulnerability suggested a deeper openness rather than mere bravado. It resonated with a generation redefining partnerships, blending new freedoms with an emerging emphasis on honesty and mutual respect.

Freedom took another form in Bruce Springsteen’s 1975 release “Born to Run.” With its urgent tempo and cinematic lyrics, the track gave voice to the longing to escape small-town limits and chase a larger life. For Boomers, it captured the thrill of getting behind the wheel with no fixed destination, the sense that the open road offered an antidote to constraint. The song’s energy still evokes that rush of possibility, speaking to a desire for autonomy that transcends its original era.

Yet by the mid-1970s, some music turned a critical eye on the consequences of success. The Eagles’ “Hotel California,” released in 1976, wrapped a haunting narrative around themes of excess, materialism, and entrapment. Its closing line about being able to “check out any time you like, but you can never leave” has often been read as a commentary on being caught in the very lifestyle or system one once thought to resist. For Boomers, it can symbolize the tension between youthful rebellion and the realities of adult responsibilities and consumer culture.

Joy, Escape, and Lasting Echoes

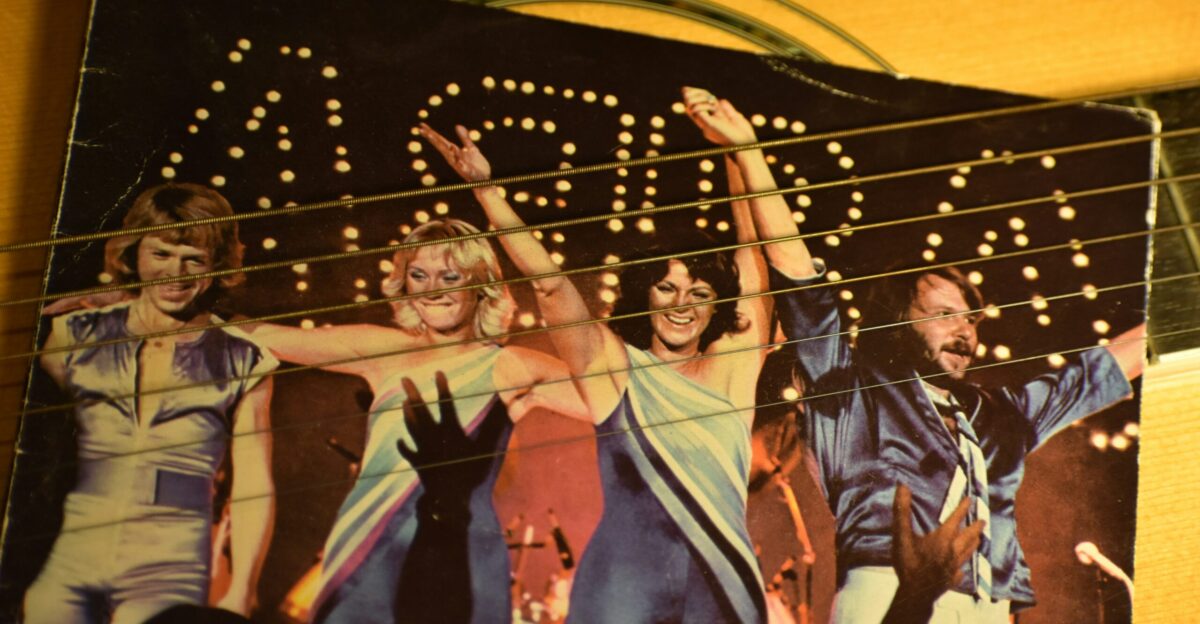

Not every defining song of the period was heavy with symbolism. Also in 1976, ABBA’s “Dancing Queen” delivered a pure burst of joy. Though the group was Swedish, the track quickly became one of the quintessential sounds of the disco era in the United States. Its celebration of a young woman lost in the moment on the dance floor captured an uncomplicated sense of fun that appealed even to listeners who otherwise dismissed disco. For many Boomers, it evokes carefree nights when music offered a simple escape from daily worries.

Taken together, these songs form more than a greatest-hits list. They trace a generation’s arc from bright optimism through protest and introspection to a later reckoning with compromise and change. For Boomers, each track can act as an emotional bookmark, tied to specific people, places, and turning points. For younger listeners, they offer a window into the moods and conflicts that shaped the late 20th century. As they continue to play on radios, streaming services, and turntables, these recordings demonstrate how sound can compress time, allowing listeners not only to remember the past but to inhabit it again, if only for a few minutes.