Every year, millions of Americans purchase Tylenol, Advil, and cold medicine without a second thought, trusting that the pill bottles on the shelf have been stored safely and inspected by regulators. But a December 26 announcement revealed something alarming: nearly 2,000 products from everyday brands had been pulled due to contamination discovered at a single Minneapolis warehouse.

The FDA’s involvement sparked urgent questions: How had rodent waste and bird droppings infiltrated products meant to heal the sick and medicate children? The story raises a more profound concern: How many Americans know their medicine cabinet might need an emergency audit?

The Scale Dawns

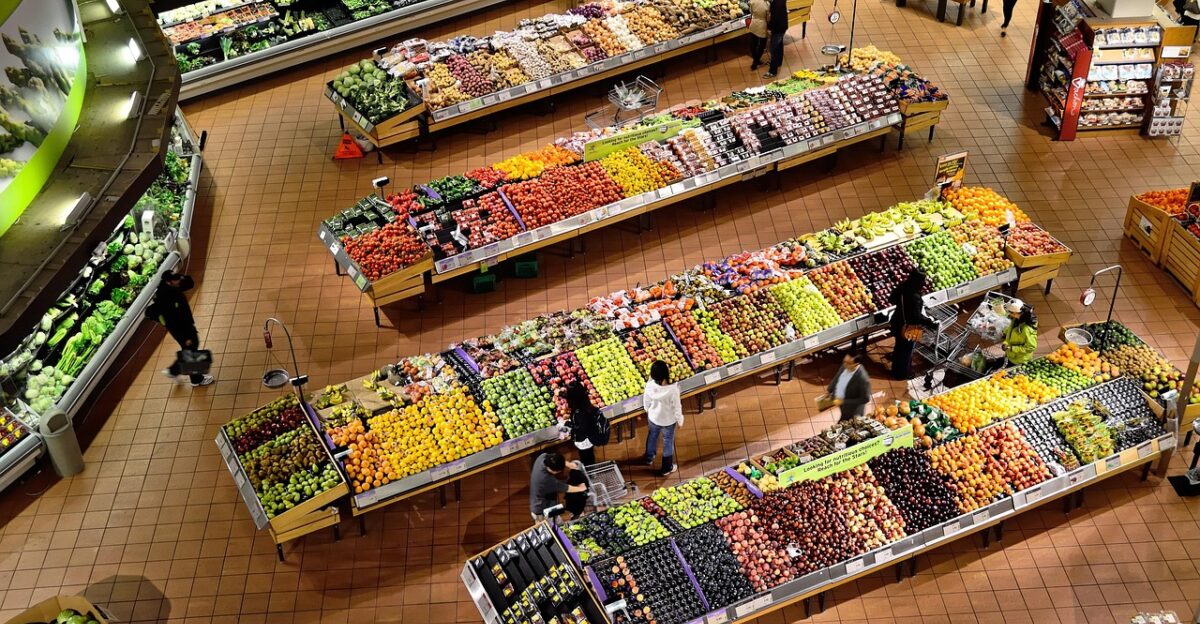

Initial reports of a warehouse problem seemed contained until the product list grew. Fifty retail locations across three states had received contaminated inventory. The recall wasn’t limited to Tylenol or Advil; it extended to Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Haribo gummy bears, Purina dog food, and over 1,990 other SKUs spanning seven FDA-regulated categories: drugs, medical devices, cosmetics, dietary supplements, human nutrition, and pet food.

One facility had become the distribution hub for contamination across three states. The sheer breadth of medications, candy, beverages, and pet food sharing the same storage space raised the stakes exponentially. How could a single warehouse compromise so many different product lines simultaneously?

Minneapolis’s Hidden Liability

Gold Star Distribution, Inc., headquartered at 1000 N. Humboldt Ave. in Minneapolis, had operated for decades as a wholesale grocery distributor serving the Upper Midwest. For years, the facility managed inventory for major brands, moving products from suppliers to regional retailers, serving as a trusted intermediary in the supply chain.

Minneapolis, Minnesota’s commercial distribution hub, had positioned the company as a critical logistics node for perishables and shelf-stable goods. Few consumers knew the name Gold Star, but nearly every household in the tri-state region had unknowingly purchased products that passed through its warehouse. The facility’s operational continuity had been taken for granted until regulators arrived.

Warning Signs Ignored

Gold Star Distribution was not new to regulatory scrutiny. In October 2018, the FDA issued a Warning Letter to the company for similar violations at the same facility, including rodent activity, insanitary conditions, and structural defects (such as a leaking roof) that had contaminated infant formula and food products. The company had been given years to correct the conditions.

Yet seven years later, federal inspectors returned to find the same fundamental problems persisting: rodent excreta, rodent urine, and bird droppings in storage areas where medical devices, drugs, and dietary supplements were held. The pattern suggested systemic failure in facility management or negligible consequences for enforcement. Regulators faced a troubling question: Why had prior warnings not forced meaningful change?

The Warehouse Investigation

On December 26, 2025, the FDA officially announced its findings from the inspection. Federal inspectors had discovered extensive evidence of infestation: “rodent excreta, rodent urine, and bird droppings in areas where medical devices, drugs, human food, pet food, and cosmetic products were held.” The facility was classified as operating under “insanitary conditions.” Products distributed between August 1 and November 24, 2025, a four-month window, were deemed potentially contaminated.

Gold Star Distribution, responding to the FDA’s findings, announced a voluntary recall of all products stored at the facility. This was not a mandatory FDA order to remove products; instead, the company initiated the recall itself, with the FDA serving as the publicizing authority. The distinction matters both legally and operationally, yet it would likely be lost on most consumers.

Minnesota’s Retail Reckoning

The Twin Cities and surrounding Minneapolis-St. The Paul metro area bore the brunt of the recall. Grocery stores, convenience stores, gas station markets, and at least one daycare facility had received products from the contaminated facility. Residents in Minnesota’s 3.7 million-person metro area faced uncertainty about items they had already purchased and stored at home.

News reports identified specific store chains and locations affected, from major chains to independent grocers. Families with young children, elderly relatives, and immunocompromised individuals living in Minnesota faced heightened health risks from Salmonella and leptospirosis exposure. The state’s Department of Health coordinated with retailers and the FDA to disseminate recall information, although questions remained about how quickly stores removed the products from their shelves.

The Consumer Awareness Gap

A sobering statistic emerged from the broader recall landscape: only 13% of Americans have ever accessed a government website for food recall information. Just 3% are subscribed to email or text recall alerts. Rutgers University behavioral scientist William Hallman, citing data from the May 2025 Food Safety Summit, highlighted the massive awareness gap.

In the Gold Star recall alone, this meant that approximately 87% of Americans, including many in the affected tri-state region, remained unaware that products in their homes might be contaminated. For a four-month distribution period (August 1-November 24), millions of consumers could have already purchased and consumed affected items before the December 26 announcement. The gap between regulatory action and public awareness had become a public health liability.

Health Risks Materialized

The contamination posed specific, documented health threats. Salmonella, the second-leading cause of foodborne illness in the U.S., according to CDC data, could cause serious and sometimes fatal infections in young children, the frail and elderly, and immunocompromised individuals. Leptospirosis, transmitted through rodent urine, causes a bacterial infection characterized by fever, muscle aches, and, in severe cases, organ failure. The FDA warned that “contact with contaminated packaging alone” could transmit pathogens.

Symptoms appear within 12-72 hours of exposure. Products were distributed from August through November; the recall came in late December, meaning exposed consumers might develop symptoms weeks after purchase, complicating diagnosis and attribution. Medical professionals treating unexplained diarrhea or fever would have no systematic way to connect cases to the warehouse contamination.

Market Ripple Effects

The recall sent shockwaves through the grocery distribution sector. Retailers faced logistical challenges, including identifying which inventory came from Gold Star, removing products from shelves, and addressing customer concerns. Major brands, including Tylenol, Advil, Coca-Cola, Pepsi, Haribo, and Purina, faced reputational exposure despite not being the source of contamination themselves. Food safety consultants noted that even though the companies themselves were not at fault, consumer perception of “recalled” brands often lingered for months.

Some consumers reported discarding entire product categories (not just affected lots) out of precaution. Supply chain vulnerabilities became a significant concern: a single warehouse operator could potentially contaminate products from dozens of manufacturers and distributors. The incident raised questions about the frequency of facility audits and the allocation of FDA inspection resources across more than 10,000 food and drug facilities nationwide.

The Prior Violation Pattern

A deeper pattern emerged upon examination: Gold Star Distribution had received a formal FDA Warning Letter in October 2018 for nearly identical violations at the same facility. The 2018 letter documented rodent activity, structural defects (including a leaking roof), and contamination of infant formula, which is among the most sensitive FDA-regulated products. The company was directed to correct conditions, yet seven years passed with apparently minimal meaningful remediation.

When the FDA returned in 2025, inspectors found rodent excreta, urine, and bird droppings once again. This was not a surprise failure but a recurring pattern of non-compliance. The implication is that either the company lacked the resources or commitment to address systemic issues, or the FDA’s follow-up enforcement had been insufficient. The question shifted from “How did this happen?” to “Why was a facility with known rodent problems still operating?”

The Recall Mechanism: Voluntary, Not Mandatory

A crucial distinction emerged in regulatory filings: Gold Star Distribution announced a voluntary recall on December 26, 2025. This is not semantics; it is a legally significant distinction. Under FDA regulations (21 CFR Part 7), a voluntary recall refers to a situation where the company initiates the removal of its products, rather than the FDA. The FDA’s role is to conduct inspections, determine if conditions warrant a recall, and publicize the company-initiated action.

Voluntary recalls represent the vast majority of U.S. recalls; mandatory recalls (FDA-ordered removals) are rare and require extensive procedural steps. Most consumers assume that an “FDA recall” means the FDA has removed the products from the market. In reality, the FDA determined that Gold Star’s facility was unsafe; therefore, Gold Star decided to recall its products. The distinction matters for liability: the company assumes responsibility, not federal regulators. Yet headlines often blur this line, leaving readers with a false impression of FDA enforcement action.

Destruction Over Returns

Gold Star instructed consumers not to return products to stores or ship them back to the company, a departure from the typical retail return process. Instead, consumers were told to destroy affected items immediately and provide proof of destruction (receipts or photographs) to claim refunds. This instruction reflected the severity of contamination: rather than risk reintroduction into the supply chain, the company prioritized removal from circulation.

Refunds required documentation sent to Gold Star at 1000 N. Humboldt Ave., Minneapolis, MN 55411, or by phone at 612-617-9800 (available 7 days/week, 8 a.m.–5 p.m. CST). The process placed a burden on consumers to verify their purchases against a 44-page product list, document destruction, and submit claims. Compliance would be low; many consumers would discard products without seeking refunds. The system revealed logistical and enforcement gaps in the execution of recalls.

Retailer Scramble and Supply-Chain Shock

Retailers across Minnesota, Indiana, and North Dakota faced immediate operational pressure. Stores had to cross-reference inventory with the 44-page FDA recall list, remove thousands of SKUs from shelves, and address customer inquiries. Some retailers issued in-store announcements; others sent direct communications to loyalty program members. But the short distribution window (August 1-November 24, 2025) meant many products had already sold before the December 26 recall announcement.

Retailers were unable to track which customers had purchased contaminated items, thereby limiting direct notification to those customers. Major chains, such as SuperValu, and regional grocers coordinated with Gold Star and the FDA on logistics. The financial impact on retailers’ staff hours, shrinkage, and restocking was not publicly quantified, but it was substantial. For small independent grocers, the recall strained resources. The incident highlighted the vulnerability of supply chains that rely on single-source distributors.

Expert Skepticism and Systemic Questions

Food safety experts raised broader systemic concerns. Dr. Robert Tauxe, former head of foodborne illness epidemiology at the CDC (in prior public statements), has noted that warehouse facility inspections are infrequent, and many facilities are not inspected in a given year. The FDA oversees approximately 10,000 food facilities and more than 200,000 drug and device manufacturers, with a limited staff. Gold Star had not been inspected for contamination issues between the October 2018 Warning Letter and the 2025 inspection, a seven-year gap.

Some experts questioned whether the FDA’s inspection frequency and follow-up enforcement were adequate to prevent recurring violations. Others pointed to the low rate of consumer awareness (13% check recalls, 3% subscribe to alerts) as a systemic failure in the communication infrastructure. Voluntary recalls, while legally valid, depend on consumer action; if 87% of affected consumers remain unaware, public health protection is compromised. The incident became a case study in regulatory gaps.

The Unresolved Question

As of January 2026, the status of Gold Star Distribution’s facility remained unclear in public disclosures. If the FDA had ordered the facility closed, would it stay open pending remediation? Would the company undergo additional inspections, or would the reinspection intervals remain the same? The deeper question persists: In a nation with 10,000+ food facilities and fragmented recall awareness, how many other warehouses harbor similar contamination undetected? The Gold Star recall exposed the gap between regulatory authority and operational oversight, as well as the discrepancy between the FDA’s inspection mandate and its resource constraints, between the legal mechanism of voluntary recalls and the reality of consumer awareness.

For millions of Americans, the message was implicit: Trust in supply-chain safety is conditional, contingent on facilities you’ll never see and inspections you’ll never know occurred. The question facing regulators, retailers, and manufacturers is whether systemic change, more frequent inspections, mandatory reporting to customers, and real-time supply-chain tracking will follow, or whether the Gold Star case will become a cautionary tale forgotten within months.

Sources:

FDA.gov – Gold Star Distribution Recall Announcement

CDC – Foodborne Illness Data

Quality Assurance Magazine – FDA Announces Major Recall After Products Found at Risk

Bring Me The News – Filth, Infestations at Minneapolis Grocery Distributor

Fielding Law – Voluntary vs. Mandatory Recalls: What’s the Difference

Rutgers University Food Safety Summit – Consumer Recall Awareness Analysis (May 2025)